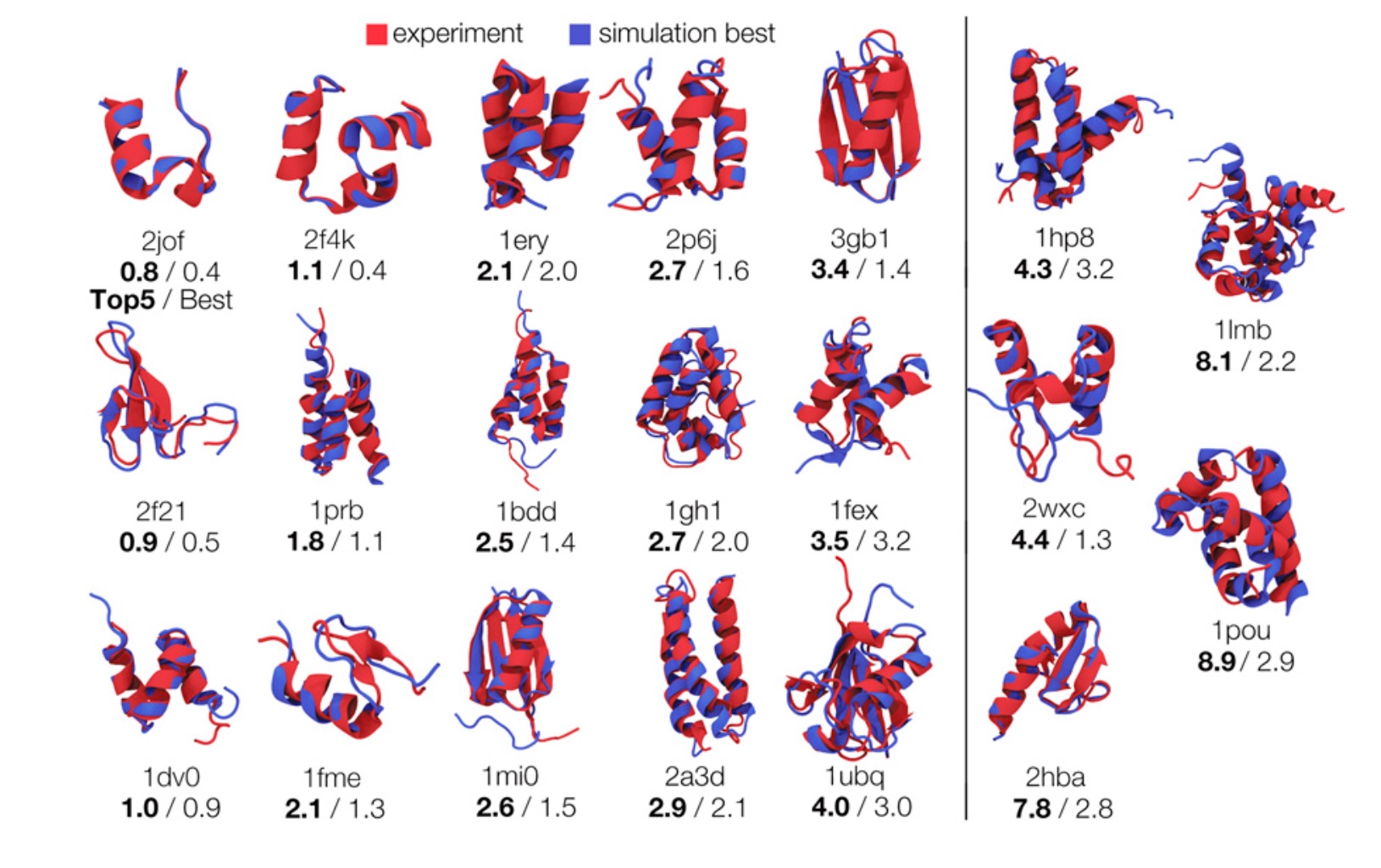

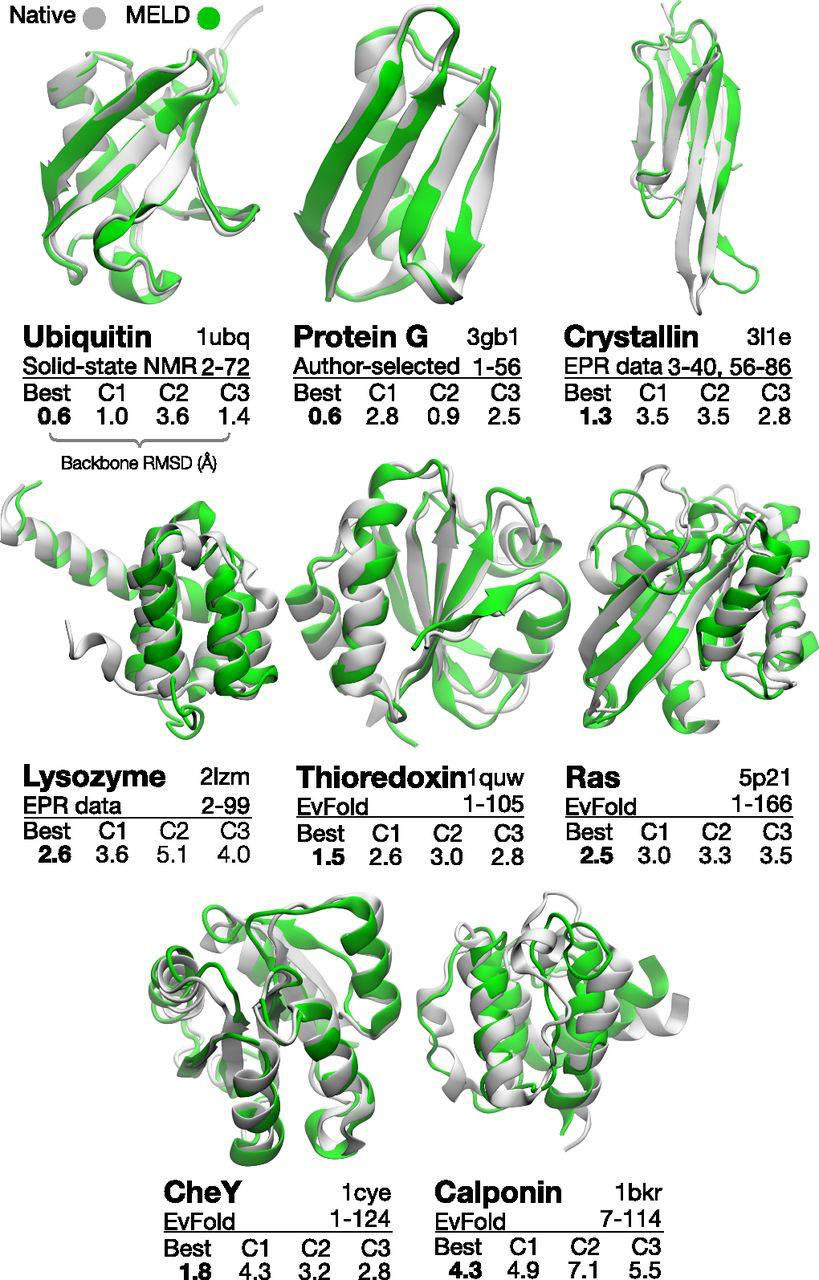

Our latest paper focuses on using weak information to infer protein structures. We use heuristic information—that proteins have hydrophobic cores, secondary structures, and form hydrogen bonds—to accelerate protein folding. The challenge is that we don't know, for example, exactly which residues form hydrogen bonds or how they pair up. However, even this uncertain knowledge is enough to accelerate conformational search by many orders of magnitude.

Adding new forces to OpenMM

Also posted on the omnia.md blog.

I often have colleagues ask why I have switched to OpenMM. As a graduate student I used GROMACS and at the start of my postdoctoral work I used Amber. Both are fine packages. So why switch?

In a word: flexibility. In a few more words: ease of development.

One component of my laboratory's research is integrative structural biology, where we are developing computational methods that can infer protein structures from sparse, ambiguous, and unreliable data. We do this by adding additional forces to the system to account for the experimental data. I won't go into the details of our research, but in this post I will outline the use of custom force classes, which are one of two ways to add custom forces to OpenMM simulations. In a future post, I will discuss the more complex—but also more flexible—route of generating an OpenMM plugin with custom GPU code.

Using custom force classes

The first—and simplest—way to add a new force to OpenMM is to use one of the seven CustomForce classes:

CustomAngleForce

CustomBondForce

CustomExternalForce

CustomGBForce

CustomHbondForce

CustomNonbondedForce

CustomTorsionForce

Each of these classes implements a particular type of interaction. Most of these interaction types are obvious from the name, but a few are worth pointing out. CustomExternalForces represent external forces that act on each atom independent of the positions of other atoms. CustomGBForce allows for the implementation of new types of generalized Born solvation models (see customgbforces.py for examples). Finally, CustomHbondForce is a very interesting class that allows for distance- and angle- dependent hydrogen bonding models—although such terms are not common in standard MD forcefields.

What makes these classes so easy to use is that they do not require writing any GPU code. One simply provides a string containing a series of expressions that describe the force to be added and OpenMM does the rest, differentiating the expression to get the forces and automatically generating the required GPU code.

As an example, the following code implements a flat-bottom harmonic potential.

import openmm as mm

flat_bottom_force = mm.CustomBondForce(

'step(r-r0) * (k/2) * (r-r0)^2')

flat_bottom_force.addPerBondParameter('r0', 0.0)

flat_bottom_force.addPerBondParameter('k', 1.0)

# This line assumes that an openmm System object

# has been created.

# system = ...

system.addForce(flat_bottom_force)Line 3 creates a new CustomBondForce, where the energy to be evaluated is given as a string. It is also possible to use more complex expression with intermediate values (see the manual for more details).

Lines 5 and 6 add per-bond parameters, which are referred to in the energy expression. In this case, for each bond that is added, we will need to specify the values of r0 and k. It is also possible to specify global parameters that are shared by all bonds using the addGlobalParameter method.

Line 11 adds our new force to the system. Don't forget this step! It's easy to overlook. Simply creating the force is not enough, it must actually be added to the system.

Adding Interactions to the system

We've now defined a new custom force. But, how do we add new interactions to our system? Again, OpenMM provides a great deal of flexibility—especially when using the python interface. The code below reads in the flat-bottom restraints to add from a text file.

# restraints.txt consists of one restraint per line

# with the format:

# atom_index_i atom_index_j r0 k

#

# where the indices are zero-based

with open('restraints.txt') as input_file:

for line in input_file:

columns = line.split()

atom_index_i = int(columns[0])

atom_index_j = int(columns[1])

r0 = float(columns[2])

k = float(columns[3])

flat_bottom_force.addBond(

atom_index_i, atom_index_j, [r0, k])Lines 13 and 14 add the new interaction. Notice that the parameters for the bond are specified as a list and that the parameters are given in the order of the calls to addPerBondParameter.

This is a very simple example, but new interactions can be added in a variety of ways: based on atom and residue types, based on proximity to other atoms or residues, based on position in the simulation cell, and so on.

Downsides of the custom force classes

There are only a few potential downsides or pitfalls when using custom force classes. The first is performance. Generally the performance of the custom force classes is quite good. However, as with all automatically generated code, it is likely that a hand-coded version would offer improved performance. However, most interactions will take only a small part of the runtime and spending considerable effort to speed up these interactions is of questionable utility.

The second downside is the limited programability. The custom force classes do not allow for loops, iteration, or if statements. Sometimes one can work around this using functions like min, max, or step (as used above). But sometimes what you want to calculate cannot be easily turned into an expression that the custom force classes use as input. In this case, one must implement a plugin with a hand-coded custom force, which is more flexible, but more involved

Summary

One of OpenMM's key strengths is the ease of adding new types of interactions. I have given a simple demonstration of how to add a custom bonded force. Other types of custom forces like torsions and new non-bonded interactions are similarly straightforward. In a future post, I will outline the steps required to create a custom plugin, which allows for more flexibility and possibly better performance, but at the cost of greater complexity.

Integrative structural biology paper published in PNAS

My lab's latest paper is now out in PNAS. This work is the first outlining our strategy for integrative structural biology, which allows us to make sense of sparse, ambiguous, and noisy information in structure determination.

Group leader named Canada Research Chair

I'm happy to announce that I've been named as one of the 2015 class of the Canada Research Chairs program.

From the CRC website:

The Canada Research Chairs Program invests approximately $265 million per year to attract and retain some of the world’s most accomplished and promising minds. Chairholders aim to achieve research excellence in engineering and the natural sciences, health sciences, humanities, and social sciences.

In addition to the CRC Chair, I was also awarded $500,000 in funding from Canada Foundation for Innovation, which will help equip my lab with state of the art instrumentation to support our research.

Kananaskis Symposium on Molecular Simulation

We just wrapped up the 6th Kananaskis Symposium on Molecular Simulation.

This three-day retreat is held in beautiful Kananaskis Country at the University of Calgary Biogeoscience Institute's Barrier Lake Field Station.

The retreat featured talks on a variety of simulation-related topics from group leaders, postdocs, and graduate students. There was also plenty of socializing and informal discussion.

This year, David Sivak of Simon Fraser University was our keynote speaker, who gave a fantastic overview of his group's research on non-equilibrium statistical mechanics and its application to biological systems.

30th Annual Darwin Day Celebration

The 30th Annual Darwin Day Celebration at the University of Calgary on Friday, February 6.

I am very excited to see that Dr. Richard Lenski will visiting. Dr. Lenski and co-workers are responsible for the E. coli Long-term Experimental Evolution Project, which has followed the evolutionary fate of several lineages of bacteria for over 60,000 generations. This amazing experiment has been on-going since 1988, and has provided an incredible real-time view of evolution in action.

New shaker arrives

Our new shaker (New Brunswick 44R) arrived today. Tara seems pleased—certainly more so than the crew I assembled to move this beast.

New pipettes have arrived

The Gilson Fairy paid a visit to the lab today and left behind a wall of new pipettes.

Advances in Enhanced Sampling Workshop

This week I'm at the Advances in Enhanced Sampling Workshop in Telluride, CO. The workshop is focused on the latest advances in conformational sampling of biomolecular (and other) systems.

The program has a great line-up of speakers and topics. I'll be giving a talk later in the week on my work on optimizing replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) simulations.

Summer School Tutorials Starting

After two days of lectures from our great external speakers, we're now moving into three days of hands-on tutorials. We have three streams:

- Introduction to MD

- Introduction to Martini and coarse-graining

- QM/MM

Molecular Simulation Summer School Kickoff

The first day of the 2nd Annual Molecular Simulation Summer School is is kicking off today.

Moraine Lake in Banff National Park

We have approximately 30 students from around Canada, plus 30 local students from Calgary. We've brought in six external speakers, in addition to a few locals:

Qiang Cui (UW Madison) QM/MM Methods

Jeff Klauda (Maryland) Lipid simulations and force fields

Siewert-Jan Marrink (Groningen) Coarse grained models of membranes

Guillaum Lamoureux (Concordia) Polarizable force fields

José Faraldo-Gomez (NIH) Free energy landscapes and most probable paths

Justin MacCallum (Calgary) Combining simulation with experimental data

Wonpil-Im (Kansas) Modeling and simulation using CHARMM-GUI

Sergei Noskov (Calgary) Enhanced sampling of membrane transporters

Peter Tieleman (Calgary) Molecular simulations and Compute Canada

After two days of lectures, we then have 2.5 days of hands-on workshops, plus a trip to Banff.

Paper Accepted

Our paper "Single molecule conformational memory extraction: P5ab RNA hairpin" has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Physical Chemistry B.

Paper accepted

Our paper on "Extracting representative structures from protein

conformational ensembles" has been accepted for publication in Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics.

Workshop on Free Energy Calculations in Drug Design

I just returned from the 2014 Workshop on Free Energy Calculations in Drug Design at Vertex Pharmaceuticals in Boston.

This meeting was interesting for me due to the number of attendees from industry---I would guess about half. I have not interacted with pharma much, so it was interesting to hear both "stories from the trenches" and thoughts about the role of free energy calculations in drug discovery.

While there was certainly plenty of skepticism about the role of free energy calculations in drug design, there was also guarded optimism. With the advent of GPU computing, these calculations are fast enough (or they will be soon) to provide answers on the timelines needed in industry. The usual question remain about force field accuracy and how to achieve sufficient sampling, but those will undoubtedly improve in the future.

Michael Shirts suggested that some of our most pressing problems are human in nature. How do we know that our codes are implemented correctly? Do we have enough testing? Are our software development practices solid enough? How do we ensure that practitioners are following best practices? What are best practices?

Overall, it was a great meeting. The next edition will be in 2016.

Website up and running

The new website is up and running, but we still need to flesh out the research section.